The High-School Juniors With $70,000-a-Year Job Offers

Companies with shortages of skilled workers look to shop class to recruit future hires; ‘like I’m an athlete getting all this attention from all these pro teams’

By Te-Ping Chen

Photographs and video by Hannah Yoon for WSJ

May 7, 2025 5:30 am ET

Read it in The Wall Street Journal

PHILADELPHIA—Elijah Rios won’t graduate from high school until next year, but he already has a job offer—one that pays $68,000 a year.

Rios, 17 years old, is a junior taking welding classes at Father Judge, a Catholic high school in Philadelphia that works closely with companies looking for workers in the skilled trades. Employers are dealing with a shortage of such workers as baby boomers retire. They have increasingly begun courting high-school students like Rios—a hiring strategy they say is likely to become even more crucial in the coming years.

Employers ranging from the local transit system to submarine manufacturers make regular visits to Father Judge’s welding classrooms every year, bringing branded swag and pitching students on their workplaces. When Rios graduates next year, he plans to work as a fabricator at a local equipment maker for nuclear, recycling and other sectors, a job that pays $24 an hour, plus regular overtime and paid vacations.

“Sometimes it’s a little overwhelming—like, this company wants you, that company wants you,” says Rios, who grew up in the Philadelphia neighborhood of Kensington around drug addicts and homelessness, and says he was determined to build a better life for himself. “It honestly feels like I’m an athlete getting all this attention from all these pro teams.”

Increased efforts to recruit high-schoolers into professions such as plumbing, electrical work and welding have helped spur a revitalization of shop classes in many districts. More businesses are teaming up with high schools to enable students to work part-time, earning money as well as academic credit. More employers are showing up at high school career days and turning to creative recruiting strategies, as well.

Employers say that as the skilled trades become more tech-infused, they anticipate doing even more recruitment at an early age, because they need workers who are comfortable programming and running computer diagnostics. “I’m not looking to hire the guy I used to have 20 years ago,” says Bob Walker, founder of Global Affinity, the Bristol, Pa.-based manufacturer who offered Rios a job. The equipment he uses is highly advanced, including a $1.7 million steel laser cutter, and he says he needs tech-savvy workers to operate it.

Angie Simon, until recently chief executive of a mechanical contractor in California, in 2021 started the “Heavy Metal Summer Experience,” a nonprofit summer program that exposes high-school students to careers in the trades, including welding, plumbing and piping. She is now executive director of the program, which is free to participants who apply. It will enroll 900 students this summer in 51 locations across the country, mostly hosted by local contractors who often hire former campers after they graduate.

“You got to stop thinking someone else is going to solve your problem,” says Simon, whose former company at times struggled to fill certain roles. “Why don’t you do something about it?”

Jenny Cantrill, 18, is working at Cannistraro, a plumbing and HVAC mechanical contractor that hosted her summer camp in Seaport, Mass. She credits the camp for piquing her interest in plumbing, and accepted Cannistraro’s job offer without looking elsewhere. “I already had that connection,” she says.

A decade ago, administrators often snubbed employers in the skilled trades who tried to get a table at a high school career fair, says Aaron Hilger, CEO of the Sheet Metal and Air Conditioning Contractors’ National Association. But with more high schools trying to give students alternatives to college, he says, that attitude has changed.

Constellation Energy, an operator of U.S. nuclear power plants based in Baltimore, offers maintenance technician and equipment-operator roles that are open to high-school graduates without four-year college degrees, and pay as much as six figures. “These are family-sustaining careers,” says Ray Stringer, a vice president overseeing workforce development at the company. Last year, Constellation launched a work-based learning program outside Chicago that invites high-school students to shadow workers at the company’s nuclear facilities while also earning community-college credit.

The company sponsors SkillsUSA, a national organization that annually convenes a week-long conference where students learning the trades can show off their skills at a venue the size of 31 football fields. The organization, founded in 1965, has seen an influx of interest from employers in the past few years, as well as students. Hundreds of companies now attend SkillsUSA each year to get their name in front of prospective hires, says the group’s executive director, Chelle Travis.

The smartest employers get a foot into high schools early on by offering internships, says Roxanne Amiot, an automotive instructor at Bullard-Havens Technical School in Bridgeport, Conn. “I tell them, don’t call me for students when they graduate, grab them now when they’re 16 or 17, or I have nobody to work for you.”

An open house at the high school last fall attracted a record 1,000 people, Amiot says, and all her classes have wait lists.

Dan Schnaufer, service and body shop director at the nearby D’Addario Automotive Group, brings on several high-school students every year to work part-time in his shop, including from Bullard-Havens. They receive academic credit for their work, and he has the benefit of seeing their skills and temperament in action and being first in line to hire them once they graduate.

“The idea of growing your own talent has gotten more critical in recent years, when you have fewer and fewer people going into this industry,” he says. At his shop, fresh high-school graduates can make around $50,000 a year, he says, and six figures within five years, without college debt.

For years, the pendulum swung too far in the direction of a college-for-all mindset, and it’s important to make sure students are made aware of all their options, says Steve Klein, a researcher who focuses on vocational education at the nonprofit Education Northwest. At the same time, as interest in vocational education rises, he worries that sentiment runs the risk of swinging too much in the other direction.

“There’s no one answer that works for all people,” he says, adding that too much of a focus on the skilled trades in high school means students risk losing exposure to broader career interests, too.

At Philadelphia’s Father Judge, all 24 graduating seniors in the welding program have job offers, each paying $50,000 and above, says welding instructor Joe Williams. More employers, he says, reach out to him every semester.

Aiden Holland, a senior at the high school, was recruited earlier this spring to become a nuclear submarine welder at a defense contractor in New Jersey, a position paying $75,000 a year. The 18-year-old says he’s grateful to have landed a job like that, with no college debt, and that his college-bound peers are often astonished to learn how much he can make with no degree.

“It feels good knowing we’re very, very much in demand,” he says.

This article was originally published in The Wall Street Journal.

CONTENT REVIEWED: May 2025

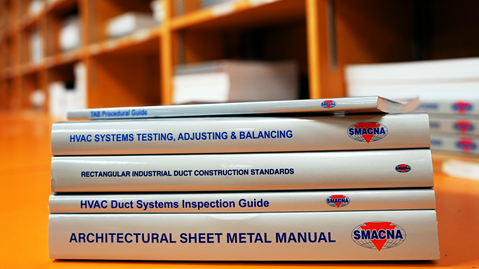

Technical Standards

Shop the SMACNA bookstore for all technical standards, including the most recent editions and recently revised manuals.

Shop Now